Astronomers have discovered the first exoplanetary system to look like our own solar system, with regularly-aligned planets.

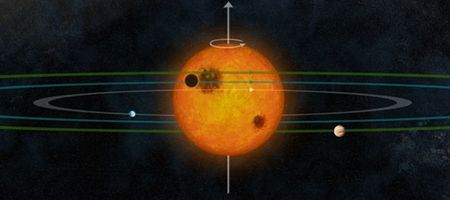

Kepler 30 – 10,000 light years away – rotates around a vertical axis and has three planets which orbit in the same plane.

“In our solar system, the trajectory of the planets is parallel to the rotation of the sun, which shows they probably formed from a spinning disc,” says MIT graduate student Roberto Sanchis-Ojeda. “In this system, we show that the same thing happens.”

The discovery may provide support a recent theory of how hot Jupiters form. Hot Jupiters lie extremely close to their stars, completing an orbit in hours or days, but typically have off-kilter orbits.

Scientists suspect that their orbits may have been knocked askew in the very early days of their system’s formation, when giant planets may have come close enough to boost some planets out of the system while bringing others closer to their stars.

Recently, scientists have identified a number of hot Jupiter systems, all of which have tilted orbits. But to really prove the theory, they’d have to find a non-hot Jupiter system, with planets circling farther from their star.

If the system were aligned like our solar system, with no orbital tilt, it would provide evidence that only hot Jupiter systems are misaligned, thanks to planetary scattering.

And, using the Kepler space telescope, that seems to be just what the team’s found. Kepler-30 is a non-hot Jupiter system with three planets, all with much longer orbits than a typical hot Jupiter.

It rotates along an axis perpendicular to the orbital plane of all three planets, making it look much like our solar system.

There could be implications for the study of how life evolved in the universe, as in order to have a stable climate suitable for life, a planet needs to be in a stable orbit.

“We’ve been hungry for one like this, where it’s not exactly like the solar system, but at least it’s more normal, where the planets and the star are aligned with each other,” says associate professor of phsics at MIT Josh Winn. “It’s the first case where we can say that, besides the solar system.”