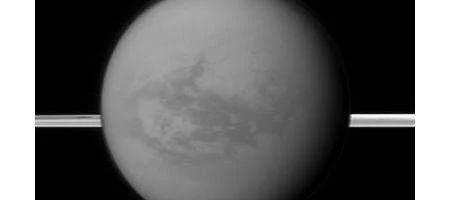

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has spotted long-standing methane lakes near the equator of Saturn’s moon Titan.

The discovery’s a surprise, because scientists had assumed that long-standing bodies of liquid would only exist at the poles. But one of the ‘tropical’ lakes appears to be about half the size of Utah’s Great Salt Lake, with a depth of at least three feet.

The team believes that the source of the methane may be an underground aquifer. “In essence, Titan may have oases,” says team associate Caitlin Griffith.

Titan has a ‘methane cycle’, rather than a water cycle like Earth. Scientists believe that liquid methane in the moon’s equatorial region evaporates and is carried by wind to the north and south poles, where cooler temperatures cause it to condense. When it falls to the surface, it forms the polar lakes.

But existing models haven’t been able to account for the abundant supply of methane, says Griffith.

“An aquifer could explain one of the puzzling questions about the existence of methane, which is continually depleted,” she says.

“Methane is a progenitor of Titan’s organic chemistry, which likely produces interesting molecules like amino acids, the building blocks of life.”

Cassini’s visual and infrared mapping spectrometer detected the dark areas in the tropical region known as Shangri-La, near the spot where the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe landed in 2005. When Huygens landed, the heat of the probe’s lamp vaporized some methane from the ground, indicating it had landed in a damp area.

The tropical lakes detected by the visual and infrared mapping spectrometer have been there since 2004. Only once has rain been detected falling and evaporating in the equatorial regions, and only during the recent expected rainy season. Scientists therefore deduce the lakes could not be substantively replenished by rain.

“We had thought that Titan simply had extensive dunes at the equator and lakes at the poles, but now we know that Titan is more complex than we previously thought,” says Cassini project scientist Linda Spilker.

“Cassini still has multiple opportunities to fly by this moon going forward, so we can’t wait to see how the details of this story fill out.”