A new analysis of a fossil discovered in 1924 indicates that human brain evolution may be connected to walking upright.

Two features of the Taung fossil — the first australopithecine ever discovered — suggest brain evolution may have resulted from a complex set of interrelated dynamics in childbirth among new bipeds.

“These findings are significant because they provide a highly plausible explanation as to why the hominin brain might grow larger and more complex,” says Florida State University evolutionary anthropologist Dean Falk.

The first feature is a ‘persistent metopic suture’, or unfused seam, in the frontal bone, which allows a baby’s skull to be pliable during childbirth as it squeezes through the birth canal.

While in great apes the metopic suture closes shortly after birth, it doesn’t fuse in humans until around two years of age, to accommodate rapid brain growth.

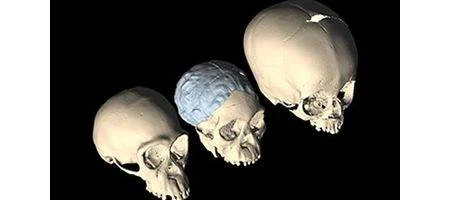

Falk also examined the fossil’s endocast, the imprint of the outside surface of the brain transferred to the inside of the skull, showing the brain’s structure.

And, concludes Falk, the persistent metopic suture is an adaptation for giving birth to babies with larger brains. It’s related to the shift to a rapidly growing brain after birth, and may be related to expansion in the frontal lobes.

“The persistent metopic suture, an advanced trait, probably occurred in conjunction with refining the ability to walk on two legs,” she says.

“The ability to walk upright caused an obstretric dilemma. Childbirth became more difficult because the shape of the birth canal became constricted while the size of the brain increased. The persistent metopic suture contributes to an evolutionary solution to this dilemma.”

The late fusing is most likely an adaptation of bipedal hominins, making it easier to give birth to babies with relatively large brains. The unfused seam is also related to the shift to rapidly growing brains after birth.

“The later fusion was also associated with evolutionary expansion of the frontal lobes, which is evident from the endocasts of australopithecines such as Taung,” Falk said.