Physicists say it’s possible to use the whole earth as a particle detector, to look for evidence of the mysterious ‘fifth force’.

A team from Amherst College and the University of Texas at Austin says it’s established new limits on long-range spin-spin interactions between atomic particles – theorized, but never seen.

Spotting them would suggest the existence of new particles, beyond those described by the Standard Model of particle physics, and would also represent the discovery of a fifth force of nature, alongside gravity and the weak, strong and electromagnetic forces.

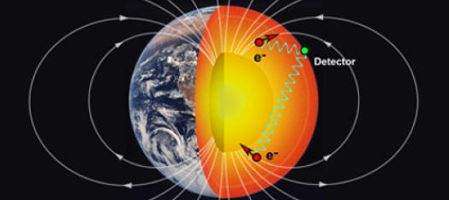

The team combined a model of Earth’s interior with a precise map of its geomagnetic field to produce a map of the magnitude and direction of electron spins throughout Earth.

Like all matter, Earth and its mantle consist of atoms, themselves made up of electrons, neutrons and protons that have spin. Earth’s magnetic field causes some electrons in the mantle’s minerals to become slightly spin-polarized, meaning the directions in which their spins point are no longer completely random, but have some net orientation.

It’s known that spins prefer to point in a particular direction.

“We know, for example, that a magnetic dipole has a lower energy when it is oriented parallel to the geomagnetic field and it lines up with this particular direction – that is how a compass works,” says Amherst professor of physics Larry Hunter.

“Our experiments removed this magnetic interaction and looked to see if there might be some other interaction that would orient our experimental spins. One interpretation of this ‘other’ interaction is that it could be a long-range interaction between the spins in our apparatus, and the electron spins within the Earth, that have been aligned by the geomagnetic field. This is the long-range spin-spin interaction we are looking for.”

So far, nobody’s found any such interaction. But, says Hunter, his team was able to infer that such so-called spin-spin forces, if they exist, must be incredibly weak – as much as a million times weaker than the gravitational attraction between the particles.

Given the high sensitivity of the technique Hunter and his team used, it may provide a useful path for future experiments that will refine the search for such a fifth force, he says.

If a long-range spin-spin force is found, it not only would revolutionize particle physics but might eventually provide geophysicists with a new tool that would allow them to directly study the spin-polarized electrons within Earth.

“If the long-range spin-spin interactions are discovered in future experiments, geoscientists can eventually use such information to reliably understand the geochemistry and geophysics of the planet’s interior,” says associate professor of geosciences at UT Austin Jung-Fu Lin.